The Future of MEV is the Future of the Crypto — Has the Importance of the MEV Track Been Underestimated?

I. Understanding MEV

When Ethereum was still using the PoW mechanism, MEV stood for “Miner Extractable Value”. Under the POS mechanism, where miners have been replaced by validators, MEV represents “Maximum Extractable Value”. Unlike under PoW where a few opaque mining pool operators controlled transaction sequencing and profited, under PoS, the right to sequence transactions within a block is open to anyone, allowing participation in block space arbitrage in an open market. Paradigm’s GP Dan classifies MEV into EIP-1559 burn, hedging, rebalance loss, and price changes before and after transactions. Simplifying the complex term MEV, any value partially/fully captured on-chain through transaction sequencing privileges can be categorized as a type of MEV. Therefore, on-chain arbitrage activities are sometimes collectively referred to as MEV. MEV is also seen as a byproduct of the blockchain and a permissionless incentive measure, which users can extract on a first-come, first-served basis.

For example, suppose user A sells 100 ETH in an AMM. Due to the AMM algorithm, the price decreases slightly with each unit sold. If a large quantity of an asset is sold, its price falls below the current market price, leading to slippage. MEV searchers, upon identifying such a transaction, buy ETH at the new price and sell it at the market price, completing arbitrage. For this to work, the searcher’s transaction must be the very next one after user A’s. Thus, MEV searchers face fierce competition, and who gets to be the first transaction before or after another often depends on the priority fee paid, aiming to be included in the block first. MEV searchers, to ensure miners package their transactions promptly, partake in the gas fee auction market, resulting in intense competition that drives the gas fee sky-high.

More traditionally, on the Ethereum blockchain, all new transactions must first wait in the public memory pool (or “mempool”) before being placed in a block and added to the blockchain. Under the previous PoW mode, miners decided which transactions to put into blocks and in what order, primarily choosing those with the highest fees, without caring about the order. However, given the massive transaction ecosystem birthed by Ethereum, MEV searchers quickly realized that profits could be gained by rearranging, inspecting, or creating new transactions based on those in the mempool. These profits are MEV. Although searchers initiate MEV, more often, a larger portion of the profit is distributed to other participants, like validators, rather than the searcher themselves.

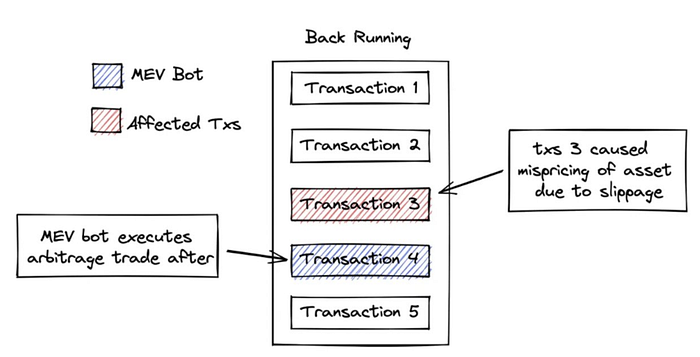

From a user and ecosystem sustainability perspective, MEV activities are broadly divided into two types: beneficial ones like arbitrage that aids price discovery and liquidations, and detrimental ones like front-running transactions or more complex sandwich attacks (inserting two new orders between a legitimate buy order, purchasing the target token at a higher price and then selling). Front-running and sandwich attacks result in ordinary DEX traders getting worse prices.

II. Overview of the MEV Track

1. Track Characteristics

The MEV track is a fundamental layer, strongly associated with all tracks related to intra-block trading. It features high-income effects, more trading scenarios mean more complex benefits for income acquisition, and relatively low risks. It coexists with the multi-L1 ecosystem expansion of the entire market.

2. Track Development

1) Solving the MEV issue is a crucial part of Ethereum’s roadmap. On November 5th of the previous year, Ethereum’s co-founder, Vitalik Buterin, released an updated Ethereum development roadmap, introducing three significant changes, including adding a new phase called “The Scourge”, ensuring reliable, fair, and trustworthy neutral transactions and addressing the MEV issue. This signifies that protocols addressing the centralization issue in MEV will gain attention, and the focus on this track will gradually increase.

2) Future development of MEV should concentrate on cross-chain MEV extraction, minimizing value leakage, reducing MEV’s potential negative impact on real users of the protocol, and ensuring fair distribution among participants.

3. Scale of the Raceway

The revenue scale of this track almost develops synchronously with the trading volume of the cryptocurrency market. Two main factors affect the scale of MEV: first, there’s a positive correlation between the frequency of arbitrage and price fluctuations; second, there’s a positive correlation between the volume of arbitrage and the total trading volume.

Considering the revenue of Flashbots, the total gross extraction profit amounts to $713.95 million, which is considered favorable MEV, impacting price discovery positively and positively influencing the core functions of DeFi and DEX trading volume. The revenue from sandwich attacks stands at $1206.11 million, viewed as unfavorable MEV. Most MEV-protected DEXes aim to control and democratize this profit share.

If we take the cumulative fee income of the top three in terms of Uniswap, Pancakeswap, and Sushi as reference points, their combined fees are $(3.24+1.2+0.77) billion, totaling $5.21 billion. It’s roughly estimated that 37% of MEV revenue is obtained through Flashbots. Besides the main DEXes, other dapps on Ethereum, as well as alt L1 and L2, also generate significant MEV income. To estimate these fees’ impact across the entire value chain, we need to analyze how MEV profits are distributed among various participants.

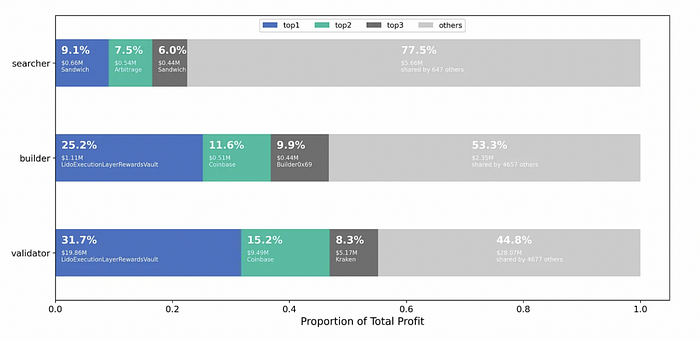

According to data from Eigenphi, in January and February 2023, MEV seekers obtained $48.3 million from all users’ transactions via wallets and RPC, of which $34.7 million went to builders. The builders then forwarded $30.3 million to the validators.

Profit distribution: Searcher- $7.3 million (17.4%); Builders — $4.4 million (10.5%); Validators — $30.3 million (72.1%). It’s evident that most of the profit (72%) is captured by downstream validators.

Of the $48.3 million, $6.3 million was burned for EIP 1559. The regular transaction priority fee transferred from wallets and RPC to builders and then to validators was $32.554 million. Regular transactions from wallets and RPC burned $227.2 million for EIP 1559.

In the 2021 bull market, the overall income ceiling was $476 million. Calculated at a conservative 10x PS, the total track scale is close to $5 billion. The scale of each subdivided raceway can be estimated proportionally: Searcher exceeds $1 billion, and Validators surpass $3.5 billion. This is just a rough estimate.

However, robots profiting from on-chain transactions might still bear the costs of many failed transactions, as well as the impacts of other off-chain hedging costs. These costs have not been included in the calculations. And this only considers the direct participants’ revenue, not accounting for the indirect participants’ market. In reality, the entire track scale will far exceed the figures mentioned.

4. Two Perspectives on MEV Racetrack Structure

(1) Value Chain

Upstream (RPC Providers): This refers to providers of on-chain transaction information and data, typically Ethereum node operators or RPC (Remote Procedure Call) service providers. These service providers offer essential data interfaces to midstream and downstream participants, allowing them to obtain transaction and block details, enabling better participation in MEV-related activities. For instance, Uniswap sends user-initiated transactions (TX) via RPC. These transactions enter the Ethereum mempool.

Midstream (Tools and Infrastructure): The midstream consists of various tools, platforms, and infrastructures that connect upstream and downstream participants, facilitating the distribution of MEV value. Such tools might include search engines, transaction builders, and relay devices, enabling searchers, builders, and block producers to discover, execute, and allocate MEV opportunities more effectively.

Downstream (MEV Profit Beneficiaries): Downstream encompasses the real beneficiaries of MEV value, including validators and other individuals or entities actually earning MEV profits. Validators are nodes participating in block validation within Proof of Stake (PoS) networks. They earn rewards from transaction fees and the network’s base interest, facilitated by midstream and upstream activities. Downstream validators include crypto exchanges (CEX), liquid staking platforms, institutional stakers, and individual stakers.

(2) Direct and Indirect Participants

The process of MEV value chain transmission.

Direct participants include Searchers, Builders, Relayers, and Block Producers also known as Validators. These entities together form the supply chain structure of MEV (Miner Extractable Value). Tools designed to serve these direct participants, such as infrastructure aimed at addressing MEV-related challenges, include Flashbots, which recently secured financing at a valuation of $1 billion, raising $60 million. They plan to use this financing to develop the SUAVE platform.

SUAVE (Single Unified Auction for Value Expression) is an infrastructure aimed at addressing MEV-related challenges. Its vision is to be a shared ordering layer across different chains. SUAVE focuses on segregating the roles of the mempool and block generation from existing blockchains, creating an independent network (ordering layer) that can plug-and-play as a mempool and decentralized block builder for any blockchain. The primary goal of SUAVE is to offer a more decentralized and fair ecosystem for users, block builders, validators, and other MEV-related participants. By separating the mempool and builder roles from other functionalities, it aims to improve efficiency across all chains, achieving a win-win: greater decentralization of the blockchain itself, increased income for validators, and more potential income and preferences for searchers/builders. Users can also transact privately at the lowest cost.

• Searchers write code, often supported by proprietary complex algorithms, to identify MEV opportunities in the mempool. They monitor public transaction pools and Flashbots’ private transaction pools, competing to submit response “bundles” to builders, accompanied by a gas bid to indicate their maximum willingness to pay (priority fee).

• Block Builders compete in real-time markets to construct blocks on behalf of validators. Any user who downloads MEV-Boost can become a Block Builder. Builders accept transactions from searchers, select profitable blocks from them, and then send these blocks to relayers via MEV-Boost.

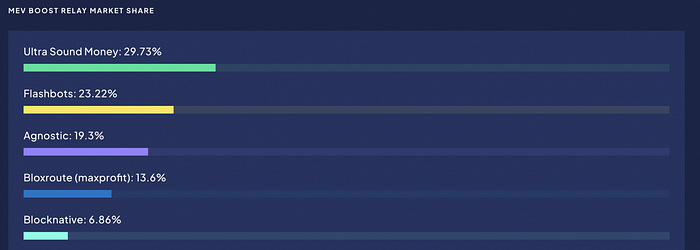

• Relayers act as intermediaries between block builders and proposers, allowing validators to offer their block space. Some relayers include transactions that were previously passed through the Tornado Cash protocol, while others exclude or “censor” these transactions. MEV relayers have been controversial due to censorship issues. In August 2022, Tornado Cash was blacklisted by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), making it illegal for U.S. citizens, residents, and companies to receive or send funds through this protocol. Validators have since had to carefully consider their choice of relayer for capturing MEV revenue, deciding whether to exclude those seen as “OFAC compliant.” Given the high number of Ethereum nodes in the U.S., many U.S.-based validators likely opt for regulatory compliance, diverging from the principle of censorship resistance. Flashbots’ own relayer was the first in MEV-Boost and chose to censor non-compliant transactions, explaining its initial dominance in OFAC-compliant block products on Ethereum. With an increasing number of relayers available, including non-censoring ones, this trend has reversed, and now less than half of the blocks are OFAC compliant. Flashbots relayer’s market share has declined to 23%.

MEV Boost Relay Market Share

• Block Producers/Validators are responsible for verifying and proposing the addition of blocks to blockchains under PoS (Proof of Stake). They often capture the most significant MEV profits. Under PoS, any user can stake 32ETH to become a Validator. Currently, Lido is the largest Validator. Validators can choose the most profitable block from multiple relayer proposals using MEV-Boost, collect the priority fee, and then one validator is randomly chosen to propose the final transaction (produce the block).

Indirect participants include almost all underlying L1, L2, and Application-layer projects that generate transactions. The Application layer is further divided into DEX (Decentralized Exchange), Lending, LSD (with MEV activities permeating the entire DeFi ecosystem, including increased transaction fees, assistance in liquidation, and helping validators increase the APY of the execution layer), and then further derived to protocols that help users avoid MEV in specific transaction scenarios (including tool providers and beneficiary protocols) such as Unibot and other TGbot protocols.

Leading projects of different participants:

Lido

MEV (Miner Extractable Value) remains significant in the Ethereum economy, constituting over 15% of all Ethereum transactions. It has increased the reward rate for stakers and validators by 25%. Lido, being the primary beneficiary among downstream validators, accounted for 31.7% of all validator profits, amounting to 19.86mln (based on data from January to February of this year). Using Lido DAO’s executive layer APR as an example, it primarily relies on MEV income, which is about one-third of the total stETH income. When on-chain transaction activity is high, this proportion can even approach 70%. Thus, it’s speculated that during a bull market, MEV revenue could still constitute 70% of the total staking income. This suggests a strong positive correlation between MEV and LSD tracks.

Uniswap

Different DEX protocols extract a share of MEV.”

MEV-related transactions on Uniswap garnered a profit of 252mln. In 2022 alone, arbitrage bots extracted at least $85 million from market price asymmetries involving the Uniswap V3 liquidity pool. Sandwich bots extracted at least $47 million from exchange users of the Uniswap V3 liquidity pool, while JIT bots extracted $6 million from Uniswap V3’s exchange fee income.

These three types of extractions have exceeded 25% of the total provider income, which is $540 million.

For genuine Uniswap users, the upcoming UniswapX, by internalizing MEV income, will substantially boost the benefits for swappers. The aggregator and RFQ off-chain order matching mechanisms in UniswapX will be a significant advancement in anti-MEV measures (even if at the cost of decentralization). For cross-chain MEV extraction, the cross-chain technology that UniswapX plans to introduce is a pivotal infrastructure.

Unibot

The current market value of the TG Bot track is less than $200 million, of which Unibot dominates with about 75% market share.

Considering Telegram’s 800 million user base, Unibot aims to tap into a huge traffic source through integrated functionalities. While the bot’s features are still in the early stages, conducting one-stop transactions within this traffic pool offers a distinct user acquisition method compared to most DeFi applications. Still, the majority of the transactions take place on Uniswap.

Currently, Unibot’s daily active users surged from about 400 to a peak of 1,700 within two weeks in July. Objectively, there’s substantial room for growth. However, this niche market usually remains active during meme trends. The overall market cap is still small, the business logic is sound, and there’s a reasonable dividend mechanism (40% revenue sharing to holders) with a high growth ceiling. In the long run, only price-insensitive users would opt for Unibot, paying an extra 5% tax compared to direct transactions on Uniswap. Such protocols have evident drawbacks. Although bots offer different settings, they usually allow users to create a dedicated wallet or link an existing one. In both cases, bots will access private keys, adding an extra layer of risk for users.

Valuation-wise

Unibot peak Vol/FDV = 12mln/182mln = 0.06

Uniswap: Vol/FDV = 429mln/6193mln = 0.069

Velo: Vol/FDV 7.5mln/100mln = 0.075

Based on the Vol/FDV metric, the market has priced Unibot within a reasonable valuation range. However, as the meme trend wanes, Unibot’s trading volume will evidently decrease.

Beyond the Ethereum ecosystem, opportunities in the MEV track also exist in other ecosystems. Furthermore, the future’s more complex cross-chain transaction scenarios will significantly amplify MEV activities.

III. Dynamic Balance of MEV and DEX Ecosystem

There’s a positive correlation between MEV transaction volume and total transaction volume. Data from Eigenphi indicates that the correlation coefficient between transaction volume (excluding arbitrage volume) and arbitrage volume is 0.6, and the correlation coefficient between transaction volume (excluding sandwich attack volume) and sandwich attack volume is 0.62. Thus, the larger the total transaction volume, the greater the MEV transaction volume. More and more DEXs are increasing their Total Value Locked (TVL) across multiple chains. Liquidity pools for the same asset pairs form across various channels, each with different transaction volumes and depths, creating new opportunities for trades and MEV.

Other factors potentially affecting MEV activity include gas fees (lower fees lead to higher potential profits, but searchers might still raise the network’s gas for a sizable transaction) and market volatility (higher volatility offers more sandwich arbitrage opportunities).

AMMs are where most of the MEV is extracted. After the emergence of Uni V3, the concept of concentrated liquidity was introduced. This allows traders to transact within a narrower price range, reducing some price discrepancies, and subsequently, reducing profit margins for certain MEV activities. Moreover, due to Uni v3’s refined price-setting mechanism, slippage tends to be smaller compared to previous versions. This theoretically reduces possible MEV profit opportunities and helps curtail some MEV activities. Simply put, as concentrated liquidity deepens at specific prices and users refine their price settings, the profits available for MEV arbitrage diminish significantly.

Emerging anti-MEV DEXs aim to protect regular users through the following mechanisms:

1) Order Transparency and Predictability — DEXs can disclose order details before submission, adopting auction mechanisms or off-chain order book matching to reduce the opportunity for front-running attacks. By revealing information in advance, traders can better predict market behavior, thereby decreasing the likelihood of attacks.

2) Time-locked Transactions — Implement time locks to ensure trades are executed only after specific blocks. This minimizes the impact of attacks like flash loans since attackers can’t execute multiple transactions within the same block.

3) Batched Transactions — DEXs can allow traders to submit multiple transactions processed as a single batch. This enhances transaction privacy and makes it harder for attackers to analyze trades.

So, how should one understand the impact of these anti-MEV measures on transaction volume? For anti-MEV DEXs, the benefits are passed onto their users. Although the reduction or conversion of sandwich attacks into non-fee-generating trades might seem like a reason for decreased volume, maintaining a positive trading environment is always beneficial for any trading system’s sustainable growth.

MEV has varied impacts on traders, liquidity providers, and miners. For traders, MEV, especially the detrimental kind, leads to increased trading costs. Traders must pay higher fees to ensure their transactions are prioritized in the blockchain, especially during network congestion.

Another concern is information asymmetry. MEV enables certain parties to use their control over transaction ordering to gain market insights, providing them with an unfair advantage. This subjects other traders to the risk of information asymmetry.

For liquidity providers (LPs), the risk of providing liquidity increases. LPs might face sandwich attack risks where the liquidity they offer is exploited by other traders, leading to losses. LPs also have to consider higher gas fees and risks to balance their profits and risks.

For miners/validators, MEV might prompt them to optimize their mining strategies to gain more transaction fees and rewards. However, this also means intensified competition as miners/validators compete for MEV, leading to rising gas fees and network congestion.

IV. Solutions to Prevent Adverse MEV

There are solutions to prevent adverse MEV from the consensus layer, execution layer, app layer, L2, and MEV tools.

At the consensus layer, Ethereum’s “The Scourge” phase is dedicated to ensuring reliable and fair credible neutral transactions and addressing MEV issues. On the transaction execution front, peer-to-peer transactions and gas-less transactions can prevent adverse MEV. Peer-to-peer transactions mean that transactions occur directly between the two parties involved, reducing the intervention of intermediaries and the possibility of malicious behavior. Gas-less transactions and separation from the mempool can reduce opportunities for malicious actors to gain an advantage by raising gas fees. Moreover, some innovative attempts provide insights into preventing adverse MEV. For example, EigenLayer introduces an MEV-boost mechanism and partial block auction in some blocks, providing new ideas and approaches for modular MEV stack design.

On the Layer 2 front, the Taiko project adopts a distinct approach — outsourcing block creation to L1, offering a potential solution using Ethereum’s base layer capabilities to address L2 MEV complexities.

At the app layer, the impact of MEV on users is minimized using Dex aggregators (in fact, the work of Dex aggregators in preventing MEV has been underrated as they place orders through different routing channels, reducing the slippage impact on spot prices, thereby preventing adverse MEV from finding trading opportunities), backrunning services, off-chain order matching, auctions, or batch processing of orders (the uniform pricing within batch processing fundamentally solves the MEV sandwiching issue. As transactions are matched directly peer-to-peer, there’s no issue of transaction sequencing).

In terms of MEV tools, Flashbots aim to alleviate the negative impacts of MEV on the entire ecosystem, such as on-chain congestion. Flashbots have launched several products, including Flashbots Auction (which encompasses Flashbots Relay), the Flashbots Protect RPC, MEV-Inspect, MEV-Explore, and MEV-Boost. The upcoming SUAVE, serving as the sequencing layer across different chains, shifts focus towards user preferences and optimizing transaction paths, creating the most efficient routes based on searchers’ desires.

V. Conclusion

From the perspective of its significance, MEV is a byproduct of block generation, and one could even argue that the future of MEV is the future of the crypto world. Strong cash flows ensure that roles such as Searchers, Builders, Relayers, and Validators, as well as tools built around these roles, have a significant income effect. However, since there aren’t many protocols issuing tokens for Searchers and Validators capturing MEV revenue, secondary investment opportunities are rare. Still, some applications at the application level will gain an extra edge by entering the MEV track. Tool projects in the primary market also have good investment opportunities. However, these tool projects need to contemplate capturing value for their protocols, rather than merely enhancing the profitability of already profitable participants.

Although adverse MEV has had some negative impacts on users, the rational application and existence of MEV can also bring about numerous positive factors. For instance, arbitrage traders ensure consistency in token pricing across AMMs, maintain stablecoin peg mechanisms, ensure smooth liquidation of DeFi loans, and keep block proposers incentivized to enhance blockchain security (by offering higher execution layer rewards).

In general, the development direction of the MEV track focuses on several key areas: cross-chain MEV capture, minimizing value leakage, alleviating the potential negative impacts of MEV on real protocol users, democratizing revenue, promoting the decentralization of sequencers, and ensuring fair distribution among participants. Presently, UniswapX’s cross-chain technology plays a pivotal infrastructure role in realizing cross-chain MEV capture. Overall, the value of the MEV market is related to more intricate trading scenarios and market fluctuations in the future, offering traders more opportunities. Potential negative impacts of MEV on real protocol users can be alleviated by adopting fair distribution and privacy protection measures at the consensus level, and by implementing off-chain order matching and reducing spot price slippage mechanisms at the protocol level. Additionally, the modularization and decentralization of MEV participants are essential components in the Ethereum roadmap, helping to build a more robust and secure MEV ecosystem.

In terms of democratizing MEV revenue, there are many areas worth exploring deeply. For anti-MEV (sandwich attack) DEXs, some of the profits originally obtained by searchers are transferred to their trading users. While anti-MEV designs might reduce or alter sandwich attacks, potentially leading to a reduction in trading volume due to adverse MEV, maintaining a good trading environment is crucial for the sustainable development of any trading system. Such positive MEV profits gradually contribute to the healthy development of the entire on-chain trading ecosystem.

A fair market competition environment provides fertile ground for innovation, and more efficient benefit distribution mechanisms and decentralized architecture are foundational to achieving this goal. Searchers and block-building technologies are inherently neutral; their impact on the entire trading environment depends on how they are utilized.

LD Capital is a leading crypto fund who is active in primary and secondary markets, whose sub-funds include dedicated eco fund, FoF, hedge fund and Meta Fund.

LD Capital has a professional global team with deep industrial resources, and focus on develivering superior post-investment services to enhance project value growth, and specializes in long-term value and ecosystem investment.

LD Capital has successively discovered and invested more than 300 companies in Infra/Protocol/Dapp/Privacy/Metaverse/Layer2/DeFi/DAO/GameFi fields since 2016.

website: ldcap.com

twitter: twitter.com/ld_capital

mail: BP@ldcap.com

medium:ld-capital.medium.com